Professor of Sociology, Emmanuel Lazega from The Paris Institute of Political Studies, (Sciences Po) gave a talk about his research on high, inconsistent and cross-level status in political networks. Prof. Lazega is a recognized researcher in the field of social networks, a recipient of the prestigious Georg Simmel Award in 2018 for his contribution to the field. He finished his PhD at the University of Geneva and did his post-doc research at Yale University. In his rich professional path, he was also the Wiarda Chair of the Faculty of Law in Utrecht (2003-2004) and is currently President of the European Academy of Sociology since 2015. Among many notable contributions, he is known for his research on the social processes in networks of corporate law partnerships, described in his book The Collegial Phenomenon: The Social Mechanisms of Cooperation Among Peers in a Corporate Law Partnership (2001).

His research is inspired by so-called “neo-structural sociology”, an approach that considers the structure, culture and collective agency in the organizational and market society. Methodologically, he integrates qualitative and quantitative methods to uncover relational infrastructures, e.g. their vertical (hierarchical relations) and horizontal (relations among peers) patterns. It allows the understanding of the social niches, multi-level institutional entrepreneurship, status competition and their role in the emergence of cooperation and collective action. The case in point was his work on studying the process of the regularization of legislative laws in EU crucial for the construction of a new transnational institution, the European Unified Patent Court, described in the paper “Collegial oligarchy and networks of normative alignments in transnational institution building”, Social Networks 48, 2017.

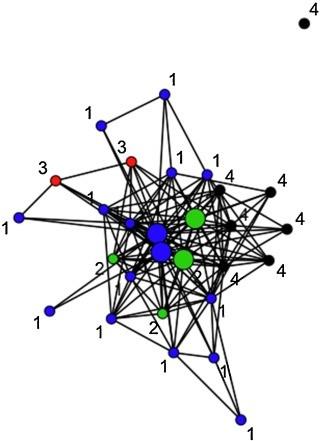

Figure 1. A collegial oligarchy of judicial entrepreneurs (Lazega, Quintane, & Casenaz, 2016)

Figure 1 shows the collegial network of judges at the Venice Forum event. The larger the node, the more central (more often nominated by his/her peers as closest to the future European Uniform position on the interpretation of patents) the judge in the network. Colors are based on the type of capitalism in the judge’s home country: 1. Continental Europe; 2. UK: 3. Scandinavia; 4. Southern Europe.

The illustration of the emergence of the new European intellectual property regime involved examples of status inconsistency (described an actor who is high on two dimensions of status that are not connected), the identifications of actors who can be seen as intermediators between levels, that is, those who take a role of multi-level “linchpins”, with the use of multi-level exponential random graph models.

The findings and interpretations of the case study fit with some concepts already revealed in Lazega’s previous work, as his work on “dual alters” (the extension of individual networks and opportunity structures), or “big fish in big pound” versus “small fish in small pound” (analogy emerged from his work on the research collaborations among scientists from different labs).

The conclusions were that reasoning in the market can be applied to political spheres, taking advantages of useful neo-structural toolkit and measurement. From the standpoint of practical implications, it is important to study multi-level networking as it can lead to non-democratic practices. For example, collegiality, unlike bureaucracy, is based on social closure. It creates network structures that enable innovation, but also corruption (patronage and clientelism, multi-level Mathew effect). The take home message from the illustration is that positions which entail conflicts of interest are actively searched and used by some actors with the aim to centralize people. Therefore, a system which allows “power to be checked by power” needs to exist in order to prevent the development of non-democratic and clientelistic society.

The other, more implicit message was the importance and potential richness that comes from studying “small” networks. Although scientists often give advantage to bigger samples (bigger networks) in their research, because they provide more possibility for generalization of findings and more robust results, in addition to being able to detect relatively small effects, we should not forget that some important networks are by definition “small” as they include the powerful elite of a selected few. Discovering how those networks function is important as they can have an important effect on politics, and society in general.

In collaboration with Tom Snijders, Lazega co-authored Multilevel network analysis for the social sciences (2016), providing methodological and theoretical insights in research of the functioning of organizational, managerial and market societies.

Blog post by Srebrenka Letina